Hurricane Season

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) defines a hurricane as “an intense tropical weather system with a well-defined circulation and maximum sustained winds of 74 mph (64 knots) or higher.”

Be prepared – have a plan!

For assistance with making an emergency plan read more here »

. 1) FEMA Ready

. 2) American Red Cross Disaster and Safety Library

. 3) ReadyNC

. 4) Town Emergency Information

. 5) HBPOIN Hurricane Emergency Plan

THB – EVACUATION, CURFEW & VEHICLE DECALS

For more information » click here

If the Town declares a mandatory evacuation, PLEASE LEAVE

General Assembly during the 2012 Session, specifically authorizes both voluntary and mandatory evacuations, and increases the penalty for violating any local emergency restriction or prohibition from a Class 3 to a Class 2 misdemeanor. Given the broad authority granted to the governor and city and county officials under the North Carolina Emergency Management Act (G.S. Chapter 166A) to take measures necessary to protect public health, safety, and welfare during a disaster, it is reasonable to interpret the authority to “direct and compel” evacuations to mean ordering “mandatory” evacuations. Those who choose to not comply with official warnings to get out of harm’s way, or are unable to, should prepare themselves to be fully self-sufficient for the first 72 hours after the storm.

No matter what a storm outlook is for a given year,

vigilance and preparedness is urged.

Previously reported – December 2024

This year’s Atlantic hurricane season is officially over

The season proved hyperactive, with five hurricanes hitting the United States.

Coastal residents can now take a collective deep breath — hurricane season is now technically over. By the books, Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 to Nov. 30. While surprises can happen, a hurricane has never hit the Lower 48 outside this window, according to records that date back to 1861. Five hurricanes slammed the United States. Four alone reached at least Florida. According to some estimates, damage exceeded $190 billion. More than 200 people died as a result of Helene, making it the deadliest mainland U.S. storm since Katrina — though thousands died in Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, when Maria hit in September 2017. The season has been a hyperactive one. That’s according to ACE, or Accumulated Cyclone Energy — a metric that estimates how much energy storms churn through and expend on strong winds. A typical hurricane season averages 122.5 ACE units. This season has featured 161.6 units — above the 159.6 unit threshold required for a season to be “hyperactive.” That’s in line with preseason forecasts, which pointed toward anomalously warm ocean waters and a burgeoning La Niña pattern. La Niñas, which begin as a cooling of water temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific, tend to feature enhanced upward motion in the air over the Atlantic.

Read more » click here

Atlantic hurricane season races to finish within range of predicted number of named storms

2024 season came roaring back despite slowdown during typical peak period

The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season, which officially ends on Nov. 30, showcased above-average activity, with a record-breaking ramp up following a peak-season lull. The Atlantic basin saw 18 named storms in 2024 (winds of 39 mph or greater). Eleven of those were hurricanes (winds of 74 mph or greater) and five intensified to major hurricanes (winds of 111 mph or greater). Five hurricanes made landfall in the continental U.S., with two storms making landfall as major hurricanes. The Atlantic seasonal activity fell within the predicted ranges for named storms and hurricanes issued by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center in the 2024 August Hurricane Season Outlook. An average season produces 14 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes. “As hurricanes and tropical cyclones continue to unleash deadly and destructive forces, it’s clear that NOAA’s critical science and services are needed more than ever by communities, decision makers and emergency planners,” said NOAA Administrator, Rick Spinrad, Ph.D. “I could not be more proud of the contributions of our scientists, forecasters, surveyors, hurricane hunter pilots and their crews for the vital role they play in helping to safeguard lives and property.” Twelve named storms formed after the climatological peak of the season in early September. Seven hurricanes formed in the Atlantic since September 25 — the most on record for this period. “The impactful and deadly 2024 hurricane season started off intensely, then relaxed a bit before roaring back,” said Matthew Rosencrans, lead hurricane forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center

Previously reported – March 2025

Hurricane season is 3 months away. Will it be as active as last year?

What to know at this early stage.

One of the first things that tipped scientists off that 2024 would be an unusually active hurricane season: excessive ocean warmth in a key region of the Atlantic Ocean. But that’s just one of many factors different as this year begins. With the Atlantic hurricane season less than three months away, forecasters are making early efforts to understand how this year may differ from the last. And while specific forecasts for the number of hurricanes can’t be accurately made this far out, forecasters can look to planetary climate patterns for clues. At least two key differences suggest odds are lower for another extremely active season: For one, the tropical Atlantic isn’t as warm as it was last year. And a La Niña (known for cooling a vast swath of the Pacific Ocean) is not expected to form during the season. But it’s still early — and current conditions don’t entirely eliminate the odds of an overactive season. In the Atlantic Ocean, hurricane season runs from June through November, typically peaking in September. Last year, hurricane season was hyperactive, based on a metric called Accumulated Cyclone Energy. There were 18 named storms and five hurricane landfalls in the United States, including the devastating Hurricane Helene. The Atlantic is cooler than last year Among the many complex puzzle pieces that start to create a picture of hurricane season — including winds, air pressure patterns, Saharan Dust and monsoonal activity — sea temperatures are a key driver. Scientists look as an early signal to what’s called the Atlantic Main Development Region, or MDR, which extends from the Caribbean to the west, and to near Africa in the east. Sea surface temperatures in the MDR have a statistical relationship with hurricane activity. In 2024, there was excessive warmth in the MDR. But it’s not currently as warm as last year, nor is it forecast to be in a few months. When the MDR is cooler, it can contribute to atmospheric conditions that aren’t particularly conducive to lots of hurricanes. Forecasts for the MDR extend to July 2025, and they suggest that while seas in the region may be somewhat above-average, the Atlantic’s most unusual warmth will be located farther north. Comparing forecasts made for July of both years shows how much warmer the MDR was predicted to be in 2024 — a prediction that turned out to be correct. If the predictions hold true this year, that might reduce the odds for a season as active as 2024. Andy Hazelton, a physical scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Environmental Modeling Center, said the cooling of the MDR is the biggest factor that has stood out to him so far. “It’s still pretty warm, especially in the Caribbean, but the subtropics (north of the MDR) look warmer overall right now,” Hazelton said. If the pattern were to continue, he said, it could put a cap on how active the season may be. La Niña may be fading During hurricane season, the Pacific and Atlantic oceans are more than distant neighbors — they’re connected by the atmosphere. What happens in one doesn’t stay there; it sends ripples to the other, shaping storm activity on both sides. One pattern that causes a Pacific-Atlantic ripple effect is known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which has three phases: El Niño, La Niña and neutral. El Niño is marked by warmer-than-average seas in the eastern Pacific, while cool seas are prominent there during La Niña. Neutral periods often occur during transitions between El Niño and La Niña, as sea temperatures temporarily become less anomalous. Early this year, the tropical Pacific entered a La Niña phase — but it’s not expected to last for much longer. The cool waters associated with La Niña can suppress rainfall and thunderstorm activity in the tropical Pacific. But as the atmosphere balances itself, increased rainfall and thunderstorm activity, as well as winds that are more conducive to hurricane formation, can occur in the tropical Atlantic. This is why, in addition to the record-warm Atlantic seas, forecasters were so concerned about the level of hurricane activity last year. But a period of weaker winds in the eastern Pacific this month has caused a substantial warming of the ocean to the west of South America. Because the winds have been less robust, a process known as upwelling — which happens when strong winds churn cool, subsurface waters to the surface — has slowed down. If the warming continues, it will put the Pacific in a much different state than it was heading into the last hurricane season. This year, a developing tongue of warm water in the eastern Pacific could have the opposite effect as it did last year, promoting rising air and more rainfall there, while having a drying effect on the Atlantic. However, predictions of El Niño and La Niña are not made equal. A phenomenon known as the “spring predictability barrier” can lead to less-skillful forecasts during spring in the Northern Hemisphere. “ENSO still has the spring barrier to cross,” Hazelton said. “But cool subsurface conditions and persistent trade winds suggest we probably won’t be getting a rapid flip or setting up for El Niño in the summer.” The bottom line: It’s still early, but 2025 looks different One thing can be said confidently at this point: So far this year, the elements that drive the Atlantic hurricane season look markedly different from 2024. The Atlantic Ocean is shaping up to have a different sea-temperature configuration than last year, with the most unusually warm seas sitting outside of the MDR. A marine heat wave — expansive blobs of unusual oceanic heat that are becoming more common in a warming climate — no longer covers the MDR, but remains active in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, areas where hurricanes derive their energy from. In the Pacific, the door may be closing on La Niña as seas warm up in the east. But a full-fledged, hurricane-halting El Niño doesn’t look particularly likely, either. Hazelton said it’s possible there will be ENSO neutral conditions during peak hurricane season. These are some of the factors forecasters will be monitoring closely as hurricane season approaches. Seasonal outlooks of hurricane activity are typically released in April and May. And while the data may change, one thing is certain: It’s never too early to prepare, especially considering the United States experienced impactful landfalls from Hurricanes Beryl, Debby, Francine, Helene and Milton last year. Read more » click here , a division of NOAA’s National Weather Service. “Several possible factors contributed to the peak season lull in the Atlantic region. The particularly intense winds and rains over Western Africa created an environment that was less hospitable for storm development.”

Read more » click here

Previously reported – April 2025

What early signs suggest about the 2025 hurricane season ahead

A marine heat wave in the Caribbean Sea may fuel an impactful hurricane season in 2025, even though seas have cooled in some areas compared to last year.

Hurricane season is just two months away, and early indications suggest it might not be as hyperactive as last year’s. Still, several factors hint that it won’t be quiet, either. For one, forecasters are looking to the oceans for signs of what could be brewing. Seas in the part of the Atlantic where storms typically form are cooler than they were at this time in 2024 — with warmer waters allowing more fuel for strengthening. But seas are nonetheless about 0.7 degrees higher than the long-term average, the eighth-warmest on record since at least 1940. A marine heat wave remains active across the Caribbean Sea and parts of the Gulf of Mexico — blobs of unusual ocean heat that, should they linger, may tip the scales toward stronger storms close to land. However, La Niña, which tends to boost hurricane activity, is fading. Still, no matter how many (or how few) storms form, it takes only one landfall to make a hurricane season devastating. Last year, five hurricanes made landfall in the contiguous United States — just the ninth season since 1851 to have at least five storm centers hit land. There were 18 storms in total, and the season was considered hyperactive, according to a metric called accumulated cyclone energy. Ahead of further key forecasts, including one from Colorado State University expected later this week, here’s The Washington Post’s assessment for the coming season, and the four key factors that will shape it: Key factors this hurricane season Sea temperatures in the Main Development Region From August to October, tropical storm and hurricane seedlings move from Africa into a vast region of warm seas in the tropical Atlantic Ocean known as the Main Development Region (MDR). The warmer it is, the more energy and moisture are available to fuel storms, allowing them to strengthen as they move through the area. Last year, the MDR was record warm, which is part of the reason forecasters expected such an active season. The MDR is cooler than it was at this time in 2024, especially near the coast of Africa, but it’s still unusually warm overall. In March, it’s been the eighth-warmest on record. Miami-based hurricane expert Michael Lowry is closely watching sea temperatures in this important region. “I certainly see some encouraging trends which suggest this upcoming season could be less active overall than recent hyperactive ones. The Atlantic remains plenty warm — much warmer than average — but after almost two years of unprecedented warmth, it’s nice to see water temperatures fall to more precedented levels,” said Lowry, a hurricane specialist with Local 10 News in Miami. Sea temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean The global climate patterns El Niño and La Niña play a critical role in determining how busy hurricane season may be. La Niña, which tends to boost hurricane activity by creating winds more conducive to their formation, has waned in recent months. The tropical Pacific Ocean is now a mix of warmer and cooler-than-average waters — moving toward what is known as a neutral phase. In other words, having neither La Niña nor El Niño. Odds are that neutral conditions will be in place for the start of hurricane season, but this time of year presents challenges for forecasting because of a phenomenon known as the spring predictability barrier. “So-called neutral years can also be quite active in the Atlantic, so unless we see a big warm-up toward El Niño over the next four or five months, the Pacific shouldn’t be a major deterrent this season,” Lowry said. A marine heat wave in the Caribbean Sea Ocean water across the Caribbean Sea and western Gulf of Mexico is well above average for the time of year — enough to qualify as a marine heat wave. These vast expanses of unusual ocean heat can affect coral reefs and the behavior of marine life but also provide more moisture and fuel for tropical weather systems. Last year, Hurricanes Helene and Milton derived their energy from a gulf affected by a marine heat wave. Both storms broke atmospheric moisture records, which contributed to extreme rainfall. The West African monsoon During June to September, heavy rains and thunderstorms bubble up over the West African Sahel. The strongest disturbances survive the long journey across Africa and emerge in the Atlantic — where they meet increasingly warm seas and strengthen further into tropical storms and hurricanes. How active the African monsoon season is helps determine how many storms may move into the Atlantic. The early indication is there will be a more active monsoon than normal. But not all monsoons are equal — last year’s episode sent storms swirling unusually far north into the Sahara, where it rains very little. Such oddities are not predictable months in advance. Other factors, such as dust from the Sahara, can reduce hurricane risk as the dry air suppresses rainfall and thunderstorm activity across the Atlantic — and can cool the ocean. But it’s not typically possible to predict dust outbreaks more than a week or so in advance. Last season, Hurricane Ernesto ingested wildfire smoke as it moved past Newfoundland, Canada. The intersection of hurricanes and wildfires will be something to watch this season, particularly as many parts of the United States continue to deal with drought impacts. What is known — and what remains uncertain It’s not possible to predict exactly when or where a tropical storm or hurricane will strike weeks or months in advance. But a broad-brush understanding of the theme of hurricane season can be developed by comparing current conditions to the past and forecast models. Forecasters analyze several key metrics and use a variety of techniques to help understand whether the season might be quiet or busy, relative to an average season, which has 14 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes (Category 3 or higher). The key predictors currently suggest that a slightly above average Atlantic hurricane season in 2025 is possible, but the hyperactive characteristics present in 2024 are fading. Lowry called hurricane season “a marathon, not a sprint” — and referred to the 1992 season, when Andrew, a hurricane with deadly impacts in South Florida, was the first and only major Atlantic hurricane of the year. He urged early preparations for any scenario. “Emergency managers and disaster planners don’t alter their plans based on the seasonal outlooks, and neither should you or your family,” Lowry said. “Prepare this year as you would any other year. It only takes one bad hurricane to make it a bad season where you live.”

Read more » click here

As the NC coast gears up for hurricane season, a big change is coming to forecast maps

We’re still a couple of months out from the start of the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season, which is the perfect time to start preparing. Gearing up for hurricane season entails more than just making sure your hurricane supplies are topped off. Making sure you can receive the latest weather updates and staying on top of what’s new for the 2025 hurricane season is just as important. The National Hurricane Center has already announced more than a few changes it’s making for the upcoming hurricane season, like updating its “cone of uncertainty” and providing an earlier window to send alerts about potential tropical activity. Here’s what to know about what’s news for the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season. The NHC is updating its Potential Tropical Cyclone system for 2025 Starting on May 15, the National Weather Service (NWS) will implement some significant changes to its Potential Tropical Cyclone advisory (PTC) system.

- Extended forecast window: The National Hurricane Center will be able to issue PTC advisories up to 72 hours before anticipated impacts, which is up from the previous 48-hour window.

- Relaxed warning criteria: The change eliminates the previous requirement that advisories could only be issued for PTCs that required land-based watches or warnings.

The experimental cone of uncertainty will be narrower The NHC says it will continue using its experimental cone graphic, which is frequently referred to as the cone of uncertainty. The graphic is meant to track the probable path of a tropical cyclone’s center. The cone is frequently misunderstood, which is one reason the NHC consistently updates the product. Here are this year’s changes.

- New symbols: The cone of uncertainty legend will now contain symbology for areas where a hurricane watch and tropical storm are in effect at the same time, marked by diagonal pink and blue lines.

- Narrower cone of uncertainty: The size of the tropical cyclone track forecast error cone will be about 3-5% smaller compared to last year.

New rip current risk map will highlight dangerous conditions stemming from hurricanes Due to an increase in surf and rip current fatalities in the United States, the NHC will provide current risk information from distant hurricanes and provide a national rip current risk map.

- Rip current risk map: To highlight the risk of dangerous conditions, NHC will provide rip current risk information from local National Weather Service and Weather Force Cast Offices in the form of a map.

Current day, next day and a composite showing the highest risk over both days will be available for areas along the East and Gulf coasts of the U.S in one page.

Read more » click here

Previously reported – May 2025

Prepare now for hurricanes, Trump warns. Here’s what NC residents, others should do. NOAA says the best time to prepare for oncoming storms is now – well before the official start of Hurricane season. National Hurricane Preparedness Week was designated by President Donald Trump on May 5, a reminder that deadly hurricanes will soon be brewing. The Atlantic Hurricane season starts June 1. Presidents dating back to at least George W. Bush have issued proclamations about the preparedness week tradition, which warns of danger ahead. According to Trump’s latest proclamation, this is “a time to raise awareness about the dangers of these storms and encourage citizens in coastal areas and inland communities to be vigilant in emergency planning and preparation.” Yet another active year is predicted, with as many as 17 named storms possible, according to a forecast from Colorado State University experts. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) says the best time to prepare for oncoming storms is now – well before the official start of the season. “Take action TODAY to be better prepared for when the worst happens. Understand your risk from hurricanes and begin pre-season preparations now.” Delaying potentially life-saving preparations could mean waiting until it’s too late. “Get your disaster supplies while the shelves are still stocked, and get that insurance checkup early, as flood insurance requires a 30-day waiting period,” NOAA recommends. NC braces for hurricane season North Carolina is No. 2. That’s not good when it comes to hurricane season predictions Here are five things you should do now: 1. Develop an evacuation plan If you are at risk from hurricanes, you need an evacuation plan. Now is the time to begin planning where you would go and how you would get there. You do not need to travel hundreds of miles. Your destination could be a friend or relative who lives in a well-built home outside flood prone areas. Plan several routes and be sure to account for your pets. 2. Assemble disaster supplies Whether you’re evacuating or sheltering-in-place, you’re going to need supplies not just to get through the storm but for the potentially lengthy aftermath, NOAA said. Have enough non-perishable food, water and medicine to last each person in your family a minimum of three days (store a longer than 3-day supply of water, if possible). Electricity and water could be out for weeks. You’ll need extra cash, a battery-powered radio and flashlights. You may need a portable crank or solar-powered USB charger for your cell phones. And lastly, don’t forget your pets! 3. Get an insurance checkup and document your possessions Contact your insurance company or agent now and ask for an insurance check-up to make sure you have enough insurance to repair or even replace your home and/or belongings. Remember, home and renters insurance doesn’t cover flooding, so you’ll need a separate policy for it. Flood insurance is available through your company, agent, or the National Flood Insurance Program. Act now, as flood insurance requires a 30-day waiting period. Also take the time before hurricane season begins to document your possessions: photos, serial numbers, or anything else that you may need to provide your insurance company when filing a claim. 4. Create a family communication plan NOAA said to take the time now to write down your hurricane plan, and share it with your family. Determine family meeting places, and make sure to include an out-of-town location in case of evacuation. Write down on paper a list of emergency contacts, and make sure to include utilities and other critical services – remember, the Internet may not be accessible during or after a storm. 5. Strengthen your home Now is the time to improve your home’s ability to withstand hurricane impacts. Trim trees; install storm shutters, accordion shutters, and/or impact glass; seal outside wall openings. Remember, the garage door is the most vulnerable part of the home, so it must be able to withstand hurricane-force winds. Many retrofits are not as costly or time consuming as you may think, NOAA said. If you’re a renter, work with your landlord now to prepare for a storm. And remember – now is the time to purchase the proper plywood, steel or aluminum panels to have on hand if you need to board up the windows and doors ahead of an approaching storm.

Read more » click here

Will hurricane season start early this year? Recent trends suggest yes

Atlantic hurricane season officially runs from June 1 through November 30, but Mother Nature does not always follow that calendar – and it looks like this year could also defy the timeline. In recent days, some forecasting models have hinted at the possibility of a head start to the 2025 season, showing the potential for storm development—specifically in the western Caribbean where conditions appear more favorable. In seven of the last 10 years, at least one named storm has formed before June 1. For comparison, there were only three years with early named storms from 2005 to 2014. After six years of storms forming early, the National Hurricane Center decided in 2021 to start issuing tropical weather outlooks beginning May 15—two weeks earlier than previously done. Some years have even seen multiple prior to the season’s start. There were two ahead-of-schedule named storms in 2012, 2016 and 2020 – and 2020 nearly had three, with Tropical Storm Cristobal forming on June 1. When a hurricane season starts early, it doesn’t necessarily mean there will be more storms. But there could be cause for concern this year, as the season’s poised to be a busy one, with an above-average 17 named storms predicted, according to hurricane researchers at Colorado State University. Early activity has largely been thanks to unusually warm waters in the Atlantic, Caribbean or Gulf basins during the spring. It’s a trend meteorologists and climate scientists have been watching for years. As our climate continues to warm, so do the oceans, which absorb 90% of the world’s surplus heat. That can have a ripple effect on tropical systems around the globe. Warm water acts as fuel for hurricanes, providing heat and moisture that rises into the storm, strengthening it. The hotter the water, the more energy available to power the hurricane’s growth. And a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, which in turn means more fuel for the tropical systems to pull from. Sea surface temperatures are already incredibly warm for this time of year, especially in the Gulf and southern Caribbean. This means any system passing through those regions could take advantage if other atmospheric conditions are favorable and develop into an early named storm. In the Caribbean, water temperatures are among some of the warmest on record for early May, and more in line with temperatures found in late June and July. The Eastern Pacific hurricane season has also seen some preseason activity in recent years, though not as frequent as the Atlantic. Part of the reason is because the Eastern Pacific season begins two weeks earlier, on May 15. In the last 20 years, the Eastern Pacific basin has only had three named tropical systems prior to that date—Andreas in 2021, Adrian in 2017 and Aletta in 2012. Another reason is the relationship between the two basins and storm formation. Generally, when the Atlantic basin is more active, the Pacific is less so due to a number of factors, including El Niño and La Niña.

Read more » click here

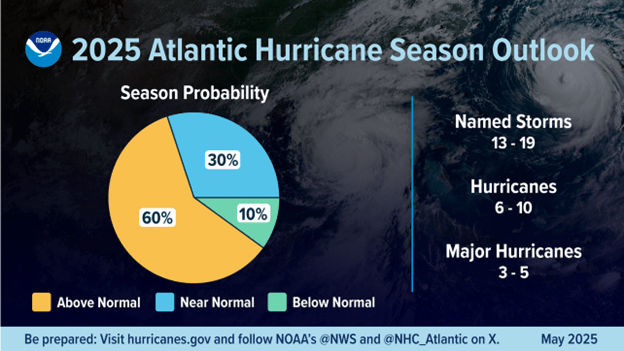

NOAA 2025 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook

The 2025 North Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook is an official product of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center (CPC). The outlook is produced in collaboration with hurricane experts from NOAA’s National Hurricane Center (NHC) and Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML). The Atlantic hurricane region includes the North Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of America.

Interpretation of NOAA’s Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook:

This outlook is a general guide to the expected overall activity during the upcoming hurricane season. It is not a seasonal hurricane landfall forecast, and it does not predict levels of activity for any particular location. Preparedness: Hurricane-related disasters can occur during any season, even for years with low overall activity. It only takes one hurricane (or tropical storm) to cause a disaster. It is crucial that residents, businesses, and government agencies of coastal and near-coastal regions prepare for every hurricane season regardless of this, or any other, seasonal outlook. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) through Ready.gov (English) and www.listo.gov (Spanish), the NHC, the Small Business Administration, and the American Red Cross all provide important hurricane preparedness information on their web sites.

NOAA does not make seasonal hurricane landfall predictions:

NOAA does not make seasonal hurricane landfall predictions. Hurricane landfalls are largely determined by the weather patterns in place as the hurricane approaches, and those patterns are usually only predictable when the storm is within several days of making landfall.

Preparedness for tropical storm and hurricane landfalls:

It only takes one storm hitting an area to cause a disaster, regardless of the overall activity for the season. Therefore, residents, businesses, and government agencies of coastal and near-coastal regions should prepare every hurricane season regardless of this, or any other, seasonal outlook.

Nature of this outlook and the “likely” ranges of activity:

This outlook is probabilistic, meaning the stated “likely” ranges of activity have a certain likelihood of occurring. The seasonal activity is expected to fall within these ranges in 7 out of 10 seasons with similar conditions and uncertainties to those expected this year. They do not represent the total possible ranges of activity seen in past similar years. Years with similar levels of activity can have dramatically different impacts. This outlook is based on analyses of 1) predictions of large-scale factors known to influence seasonal hurricane activity, and 2) long-term forecast models that directly predict seasonal hurricane activity. The outlook also takes into account uncertainties inherent in such outlooks.

Sources of uncertainty in the seasonal outlooks:

- Predicting the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phases, which include El Niño and La Niña events and ENSO-neutral and their impacts on North Atlantic basin hurricane activity, is an ongoing scientific challenge facing scientists today. Such forecasts made during the spring generally have limited skill.

- Many combinations of named storms (tropical and subtropical storms), hurricanes, and major hurricanes can occur for the same general set of conditions. For example, one cannot know with certainty whether a given signal may be associated with several shorter-lived storms or fewer longer-lived storms with greater intensity.

- Model predictions of sea-surface temperatures (SSTs), vertical wind shear, moisture, atmospheric stability, and other factors known to influence overall seasonal hurricane activity have limited skill this far in advance of the peak months (August-October) of the hurricane season.

- Shorter-term weather patterns that are unpredictable on seasonal time scales can sometimes develop and last for weeks or months, possibly affecting seasonal hurricane activity.

2025 North Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook Summary

a) Predicted Activity

NOAA’s outlook for the 2025 Atlantic Hurricane Season indicates that an above-normal season is most likely, with a moderate probability that the season could be near-normal and lower odds for a below-normal season. The outlook calls for a 60% chance of an above-normal season, along with a 30% chance for a near-normal season and only a 10% chance for a below-normal season. See NOAA definitions (https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/outlooks/Background.html) of above-, near-, and below-normal seasons. The 2025 outlook calls for a 70% probability for each of the following ranges of activity during the 2025 hurricane season, which officially runs from June 1st through November 30th:

- 13-19 Named Storms

- 6-10 Hurricanes

- 3-5 Major Hurricanes

- Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) range of 95 to 180% of the median

The seasonal activity is expected to fall within these ranges in 70% of seasons with similar conditions and uncertainties to those expected this year. These ranges do not represent the total possible ranges of activity seen in past similar years. These expected ranges are centered above the 1991-2020 seasonal averages of 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes. Most of the predicted activity is likely to occur during August-September-October (ASO), the peak months of the hurricane season. The North Atlantic hurricane season officially runs from June 1st through November 30th. This outlook will be updated in early August to coincide with the onset of the peak months of the season (ASO). b) Reasoning behind the outlook This 2025 seasonal hurricane outlook reflects the expectation of factors during ASO that have historically produced active Atlantic hurricane seasons, though some were not as active, resulting in a range of activity. The main atmospheric and oceanic factors for this outlook are:

- The set of conditions that have produced the ongoing high-activity era for Atlantic hurricanes which began in 1995 are likely to continue in 2025. These conditions include warmer sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) and weaker trade winds in the Atlantic hurricane Main Development Region (MDR), along with weaker vertical wind shear, and a conducive West African monsoon. The oceanic component of these conditions is often referred to as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), while the ocean/atmosphere combined system is sometimes referred to as Atlantic Multidecadal Variability (AMV). The MDR spans the tropical North Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. Currently observed SSTs in the MDR are similar to those normally observed in mid-June. Saharan Air Layer outbreaks typically mitigate some of the activity early in the season, but it is not known if this will significantly affect activity during the peak months. Tradewinds are weaker than normal which contributes to lower vertical wind shear. The upper-level circulation with the West African Monsoon is near average, though monsoon rainfall is predicted to be shifted northward and be potentially above-average for the entire season.

- The most recent forecast from the NOAA Climate Prediction Center indicates ENSO-neutral conditions are likely through the hurricane season. During the peak months (ASO), the odds are highest for ENSO-neutral (54%), with moderate probabilities for La Niña (33%), and low chances of an El Niño event (13%) occurring. During a high-activity era, ENSO-neutral is typically associated with above-average levels of hurricane activity. La Niña events tend to reinforce those high-activity era conditions and further increase the likelihood of an above-normal hurricane season, while most of the inactive seasons are associated with El Niño events.

Read more » click here

NOAA predicts above-normal 2025 Atlantic hurricane season Above-average Atlantic Ocean temperatures set the stage NOAA’s outlook for the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season, which goes from June 1 to November 30, predicts a 30% chance of a near-normal season, a 60% chance of an above-normal season, and a 10% chance of a below-normal season. The agency is forecasting a range of 13 to 19 total named storms (winds of 39 mph or higher). Of those, 6-10 are forecast to become hurricanes (winds of 74 mph or higher), including 3-5 major hurricanes (category 3, 4 or 5; with winds of 111 mph or higher). NOAA has a 70% confidence in these ranges. “NOAA and the National Weather Service are using the most advanced weather models and cutting-edge hurricane tracking systems to provide Americans with real-time storm forecasts and warnings,” said Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick. “With these models and forecasting tools, we have never been more prepared for hurricane season.” “As we witnessed last year with significant inland flooding from hurricanes Helene and Debby, the impacts of hurricanes can reach far beyond coastal communities,” said Acting NOAA Administrator Laura Grimm. “NOAA is critical for the delivery of early and accurate forecasts and warnings, and provides the scientific expertise needed to save lives and property.”  Factors influencing NOAA’s predictions

Factors influencing NOAA’s predictions

The season is expected to be above normal – due to a confluence of factors, including continued ENSO-neutral conditions, warmer than average ocean temperatures, forecasts for weak wind shear, and the potential for higher activity from the West African Monsoon, a primary starting point for Atlantic hurricanes. All of these elements tend to favor tropical storm formation. The high activity era continues in the Atlantic Basin, featuring high-heat content in the ocean and reduced trade winds. The higher-heat content provides more energy to fuel storm development, while weaker winds allow the storms to develop without disruption. This hurricane season also features the potential for a northward shift of the West African monsoon, producing tropical waves that seed some of the strongest and most long-lived Atlantic storms. “In my 30 years at the National Weather Service, we’ve never had more advanced models and warning systems in place to monitor the weather,” said NOAA’s National Weather Service Director Ken Graham. “This outlook is a call to action: be prepared. Take proactive steps now to make a plan and gather supplies to ensure you’re ready before a storm threatens.”

Improved hurricane analysis and forecasts in store for 2025

NOAA will improve its forecast communications, decision support, and storm recovery efforts this season. These include:

- NOAA’s model, the Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System, will undergo an upgrade that is expected to result in another 5% improvement of tracking and intensity forecasts that will help forecasters provide more accurate watches and warnings.

- NOAA’s National Hurricane Center (NHC) and Central Pacific Hurricane Center will be able to issue tropical cyclone advisory products up to 72 hours before the arrival of storm surge or tropical-storm-force winds on land, giving communities more time to prepare.

- NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center’s Global Tropical Hazards Outlook, which provides advance notice of potential tropical cyclone risks, has been extended from two weeks to three weeks, to provide additional time for preparation and response.

Enhanced communication products for this season

- NHC will offer Spanish language text products to include the Tropical Weather Outlook, Public Advisories, the Tropical Cyclone Discussion, the Tropical Cyclone Update and Key Messages.

- NHC will again issue an experimental version of the forecast cone graphic that includes a depiction of inland tropical storm and hurricane watches and warnings in effect for the continental U.S. New for this year, the graphic will highlight areas where a hurricane watch and tropical storm warning are simultaneously in effect.

- NHC will provide a rip current risk map when at least one active tropical system is present. The map uses data provided by local National Weather Service forecast offices. Swells from distant hurricanes cause dangerous surf and rip current conditions along the coastline.

Innovative tools for this year

- NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Services (NESDIS), in collaboration with NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations and NOAA Research, is deploying a new, experimental electronically scanning radar system called ROARS on NOAA’s P-3 hurricane hunter research aircraft. The system will scan beneath the plane to collect data on the ocean waves and the wind structure of the hurricane.

- NOAA Weather Prediction Center’s experimental Probabilistic Precipitation Portal provides user-friendly access to see the forecast for rain and flash flooding up to three days in advance. In 2024, Hurricane Helene caused more than 30 inches of extreme inland rainfall that was devastating and deadly to communities in North Carolina.

NOAA’s outlook is for overall seasonal activity and is not a landfall forecast. NOAA also issued seasonal hurricane outlooks for the eastern Pacific and central Pacific hurricane basins. NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center will update the 2025 Atlantic seasonal outlook in early August, prior to the historical peak of the season.

Read more » click here